Types Of POTS

Let’s talk about three of the more studied proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms that help explain some of what our community experiences (Mar & Raj, 2020)! We can’t fairly say that these include all that our community experiences, as there is still a great deal that we don’t fully understand about this syndrome. We do hope that, despite this, all proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms will become clearer with additional research in the coming years. There is a great deal of overlap between these three proposed mechanisms. As a result, some in our community may find that they meet criteria within each proposed “type” of POTS. Some refer to these variants of POTS as distinct phenotypes, or endophenotypes, but we will be sticking to “types” of POTS for simplicity (Mar et al., 2020). More available research over the last year has shed more light on these types of POTS, and we plan to have the new information here for everyone to review by July 2025.

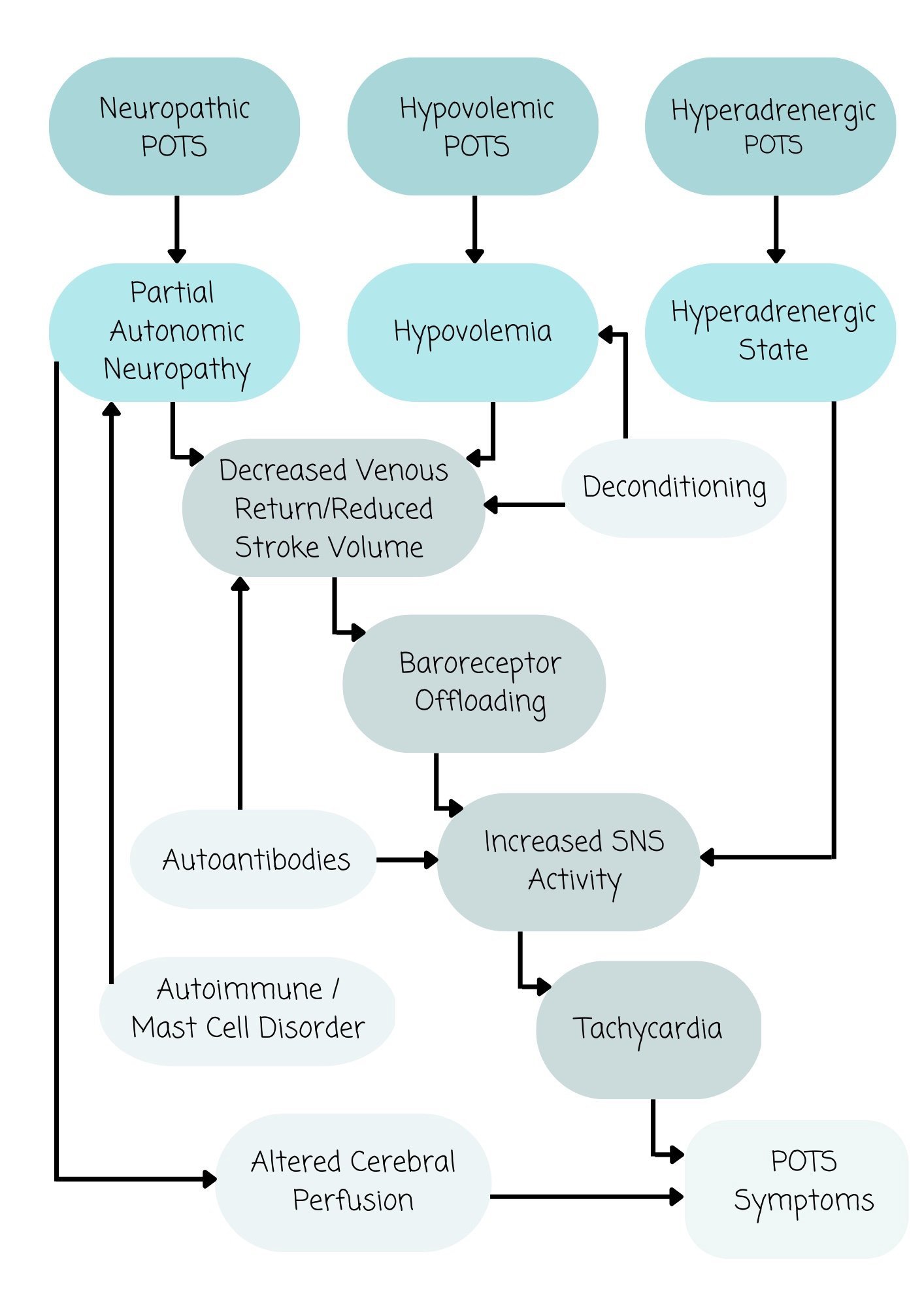

Proposed Links Between Each Mechanism

Image permissions obtained from Annual Reviews. Source: Mar, P. L., & Raj, S. R. (2020). Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Mechanisms and new therapies. Annual Review of Medicine, 71(1), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-041818-011630

Neurogenic POTS

Individuals in our community with signs/symptoms consistent with neuropathic POTS often present with partial autonomic neuropathy of some vasculature (blood vessels); this can contribute to blood pooling in various parts of the body (Mar et al., 2020). Blood pooling for individuals with POTS often can be seen in the lower extremities, pelvis, and splanchnic (abdominal) region (Mar et al., 2020).

Often, this partial autonomic neuropathy that contributes to blood pooling can lead to decreased venous return and decreased stroke volume, baroreceptor offloading, increased SNS activity, tachycardia, and a plethora of other POTS symptoms (Mar et al., 2020). Some of these other POTS symptoms can occur secondary to altered cerebral perfusion (Mar et al., 2020).

Researchers have noticed the presence of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) impairment (malfunctioning) in individuals with neurogenic POTS; this was seen when individuals with POTS responded quite differently to norepinephrine at SNS synapses as compared to healthy subjects (Jacob et al., 2000).

Hyperadrenergic POTS

Individuals in our community with signs/symptoms consistent with Hyperadrenergic POTS often present with increased SNS activity, where they have measurable elevated plasma norepinephrine levels upon standing (Mar et al., 2020).

These levels of norepinephrine individuals with hyperadrenergic POTS have are significantly higher when assuming an upright position, as they can reach or exceed 800 pg/ml; in contrast, individuals who are healthy and do not have POTS have norepinephrine levels that reach around 400-500 pg/ml when assuming a standing position (Mustafa et al., 2011; Jacob et al., 2000).

Individuals with this type of POTS often present with palpitations secondary to the increase in SNS activity, fight or flight response. The orthostatic tachycardia experienced by individuals with this type of POTS is driven, primarily, by elevated norepinephrine levels (hyperadrenergic state).

It is important to note individuals in within the POTS community may experience symptoms that overlap and include aspects of each type of POTS, with some experiencing elevated norepinephrine levels “secondary to partial autonomic neuropathy or hypovolemia” (Mar et al., 2020).

Hypovolemic POTS

A persistent hypovolemic state (where individuals have a low blood volume) is commonly seen within the POTS community (Mar et al., 2020).

What’s confusing for many providers is that despite this low blood volume, individuals with POTS often have low levels of plasma renin and aldosterone (Mar et al., 2020). Low levels of renin and aldosterone lead to less salt and water absorption by the kidneys, and more water and salt excretion (as urine). This is not helpful when we are trying to increase our blood volume through our increased salt and water intake, hoping desperately to retain salt and water, not excrete them! This is one of the reasons why it can be recommended for some individuals in our community to increase their salt and water consumption.

The persistent hypovolemic state is what contributes to a decrease in venous return, decrease in stroke volume, increased SNS activity, reduced cerebral perfusion (blood flow to the brain), and tachycardia (Mar et al., 2020).

Sources:

Jacob G,Costa F,Shannon JR,et al.(2000).Theneuropathicposturaltachycardiasyndrome.N.Engl.J. Med. 343:1008–14

Jacob G, Ertl AC, Shannon JR, et al. (1998). Effect of standing on neurohumoral responses and plasma volume in healthy subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 84:914–21

Mar, P. L., & Raj, S. R. (2020). Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Mechanisms and new therapies. Annual Review of Medicine, 71(1), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-041818-011630

Mustafa HI, Garland EM, Biaggioni I, et al. (2011). Abnormalities of angiotensin regulation in postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm 8:422–28